Blogs | Dawn Journal | October 31, 2017

Dear Frankendawns, Skeledawns, and all other Dawn-or-Treaters,

Dawn's long and productive expedition in deep space is about to enter a new phase.

Building on the successes of its primary mission and its first extended mission, NASA has approved the veteran explorer for a second extended mission. Dawn will undertake ambitious new investigations of dwarf planet Ceres, its permanent residence far from Earth.

It was not a foregone conclusion that Dawn would conduct further operations. In part, that's because it is only one of many exciting and important missions NASA has underway, and more are being designed and built. But the universe is a big place, as you may have noticed if you've ever gazed in awestruck reflection at the night sky (or had to search for a parking space in Los Angeles). It simply isn't possible to do everything we want. Entrusted with precious taxpayers' dollars, NASA has to make well-considered choices about what to do and what not to do.

In addition, as we have discussed in detail, Earth's ambassador to two giants in the main asteroid belt has had to contend with severe life-limiting problems. Dawn's reaction wheels have failed, and now it has consumed most of its original small supply of hydrazine that it uses in compensation. It has also expended most of the xenon propellant for its uniquely capable ion propulsion system. It was not clear that a truly productive future would be possible for this aged, damaged ship with some supplies that are so limited. Fortunately, Dawn has endless supplies of creativity, ingenuity, dedication and enthusiasm.

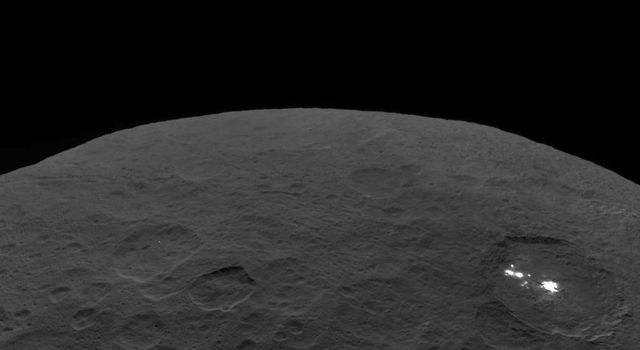

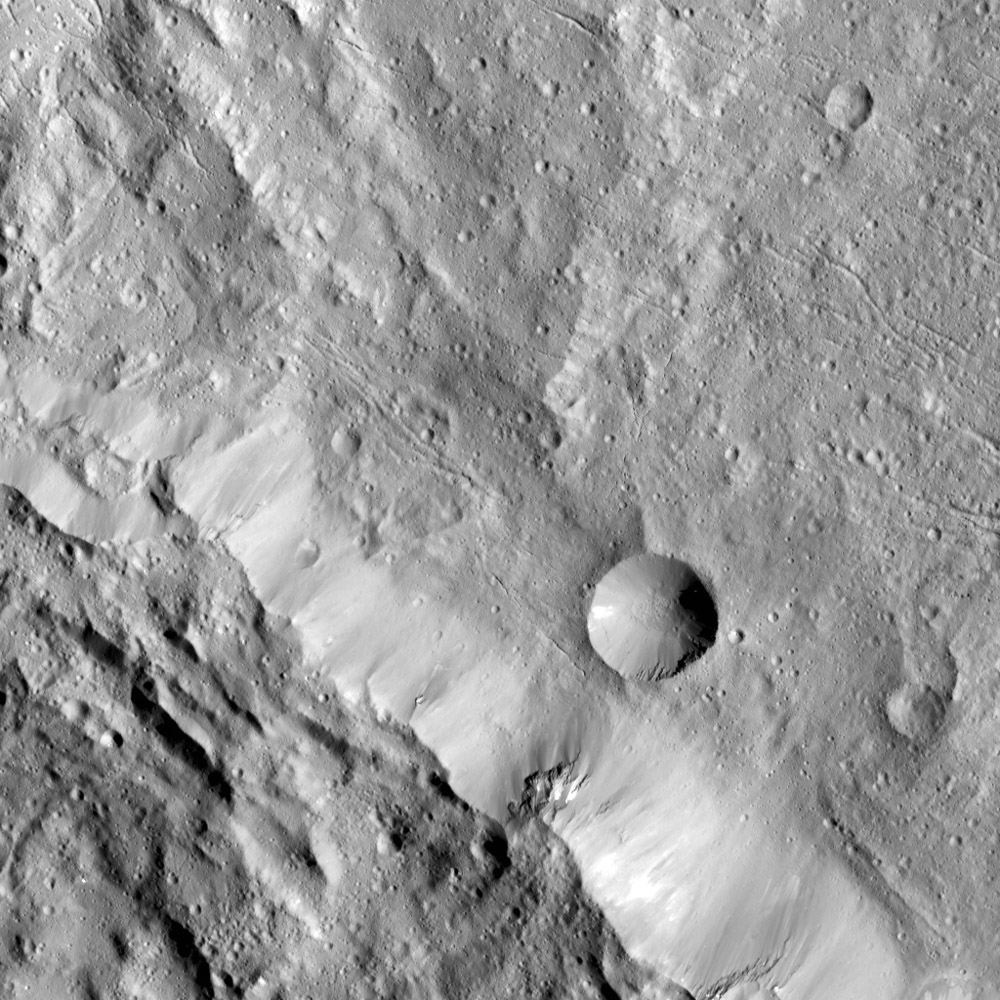

For several months, the flight team has been studying the feasibility of flying the spaceship closer to Ceres than had ever been seriously considered. Dawn spent more than eight months in 2015-2016 circling about 240 miles (385 kilometers) above the dwarf planet. It had spectacular views of mysterious landscapes and acquired a wealth of data far beyond what the team had anticipated. Then Dawn flew to a higher altitude during its first extended mission for new observations. Now engineers are making progress on ways to operate the spacecraft in an elliptical orbit that would allow it to swoop down to below 125 miles (200 kilometers) for a few minutes on each revolution. Their results so far are very encouraging. There are still many complex technical problems to solve, and months of additional work remain. Dawn can wait relatively patiently in its current orbit, where it expends hydrazine quite parsimoniously as it measures cosmic rays.

The promising potential for observing Ceres in elliptical orbits from closer than ever before makes a second extended mission there extremely attractive. NASA and the panel of scientists and engineers convened to provide an independent, objective assessment concluded that further exploration of Ceres would be the most valuable assignment for the spacecraft. It is noteworthy that Dawn is the only spacecraft ever to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations and even now, having significantly exceeded its original objectives, has the capability to leave Ceres and pay a brief visit to a third (although it does not have enough xenon left to orbit a third), but the prospects for new discoveries at Ceres are too great to pass up.

Ceres is not only the largest object between Mars and Jupiter but also certainly one of the most intriguing. In fact, motivated by what Dawn has found, there is now great interest in the possibility of sending a lander there someday. Anything more Dawn can do to learn about Ceres or to help pave the way for a subsequent mission will be of great importance.

Ceres is just too fascinating to abandon! Dawn has already revealed the dwarf planet to be an exotic world of ice, rock and salt, with organic materials and other chemical constituents, and now we can look forward to more discoveries. After all, the benefit of having the capability to orbit a distant destination, rather than being limited to a quick glimpse during a fleeting flyby, is that we can linger to scrutinize it and uncover even more of the secrets it holds. (Some readers may also draw inspiration from Ceres' ingredients to concoct recipes for treats to give out to Halloween visitors.)

In addition to the possibility of observing Ceres from unprecedentedly close, there are other benefits to keeping our sophisticated probe at work there. For now, let's consider two of them, both related to how long it takes Ceres to complete its stately orbit around the sun. One Cerean year is 4.6 terrestrial years.

The dwarf planet carries its robotic moon with it as it follows its elliptical path around the sun. In fact, all orbits, including Earth’s, are ellipses. Ceres’ orbit is more elliptical than Earth’s but not as much as some of the other planets. The shape of Ceres’ orbit is between that of Saturn (which is more circular) and Mars (which is more elliptical). (Of course, Ceres’ orbit is larger than Mars’ and smaller than Saturn’s, but here we are considering how much each orbit deviates from a perfect circle, regardless of the size.)

When Dawn arrived at Ceres in March 2015, they were 2.87 AU from the sun. That was well before the dwarf planet's orbit carried them to the maximum solar distance of 2.98 AU in January 2016. Now, with the second extended mission, the spacecraft will still be operating when Ceres reaches its minimum solar distance of 2.56 AU in April 2018. Dawn will keep a sharp eye out for any changes caused by being somewhat closer to the sun.

The extension also will give scientists the opportunity to examine Ceres with the different lighting caused by the change of seasons. Ceres' slower heliocentric orbit than Earth's means seasons last longer on that distant world. It was near the end of autumn in the southern hemisphere when Dawn took up residence at Ceres. Winter came to that hemisphere on July 24, 2015, when the sun reached its greatest northern latitude. The sun crossed the equator, bringing spring to the southern hemisphere, on Nov. 13, 2016, and summer begins on Dec. 22 of this year. Autumn, when the sun will leave the southern hemisphere, is more than one (terrestrial) year later. Most of Dawn's observations so far were made with the sun in the northern hemisphere. Now Dawn will have new opportunities to see the southern hemisphere with similar illumination.

In the coming months, as the team develops and refines its plans, we will describe how they will pilot the ship down to very low altitudes and what new measurements they will make. Before the new phase gets underway, however, you can explore Ceres (and other planets) yourself with Google maps (some functions don't work in some web browsers). Even though it does not use Dawn's sharpest photos, it should be more than adequate for most of your navigational needs. (It isn't quite adequate for Dawn's needs, but that's no cause for worry, because JPL navigators employ somewhat more sophisticated and accurate methods.)

What will Dawn find when it ventures closer to the ground than ever before? What will the new perspectives reveal about a strange world from the dawn of the solar system? What new challenges will the adventurer confront as it pushes further into uncharted territory? We don't know, but stay onboard as we find out together, for that is an essential element both of the tremendously successful process of science and the powerful thrill of exploration.

Dawn is 21,600 miles (34,700 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 2.47 AU (229 million miles, or 369 million kilometers) from Earth, or 970 times as far as the moon and 2.49 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 41 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

2:30 p.m. PDT October 31, 2017

TAGS:DAWN, CERES, EXTENDED MISSION